One people’s historic right is another’s historic wrong, and all the more when it is based on a wrong history.

Near the start of our present woes in Palestine, when the genocide of Gaza was still a half-born twinkle in Benjamin Netanyahu’s eye, the 44th president of the United States of America emerged from occultation to deliver unsought advice. Barack Hussein Obama, Jr. took to Medium, the wisdom-enjoyer’s Twitter, to share some finely polished pearls from the oyster of both-sidesism. “[A]ll of us,” announced the voice of reason and moderation, “need to do our best to put our best values, rather than our worst fears, on display.” What does putting those “values” on “display” entail?

It means recognizing that Israel has every right to exist; that the Jewish people have claim to a secure homeland where they have ancient historical roots….

It means acknowledging that Palestinians have also lived in disputed territories for generations….

You may wonder whether historical “recognitions” and “acknowledgments” really count as our best “values,” but this at least was an improvement over the modern-day repeaters of the hoaxes of Joan Peters, who still don’t think that Palestinians have in Palestine any history at all. Better in tone, that is, but not in substance. “Disputed territories” is a clever touch, skillfully avoiding having to mention the nature of the dispute, let alone its merits (much less the fact that there’s an illegal occupation), while giving full faith and credit to the Israeli claim on sovereignty. The indefinite plural “generations,” while technically correct, is accurate to a fault. Still, Mr. Obama’s phrasing may be more right than even he knew. Such historical views as stated really are a question of one’s “values”—of values pre-determining one’s view of history, instead of vice-versa.

The right-wing smears on Barack Obama as some sort of pro-Palestine sleeper agent (don’t you know he once attended a talk by Edward Said?) were always delirious and insane, but he was reportedly a friend of Rashid Khalidi, and he seems to grasp that Israel’s founding came at the expense of the people living there before it. He is a man who should know better, in other words. And yet even when paying lip-service to Palestinians’ basic humanity, and as a political retiree with no diplomatic or electoral pressures to be shy for, Mr. Obama could not help but take the zionist framing as a given: that the land of Palestine really is the rightful inheritance of the Jewish people, and any rights the Palestinian Arabs may have are really more like that of squatters. It’s a framing which public figures and politicians and media never tire of repeating. Even in the New York Times, the supposed “liberal” paper of record, the Israelis’ habit of stealing property illegally and driving Palestinians from their homes is described in terms no stronger than “seizing land previously used [sic] by Palestinians.”

Within Israel, this framing forms a national creed with constitutional legal status, defining the land as “the historical homeland of the Jewish people,” in which the right of self-determination is “unique to the Jewish people.” Prime minister Netanyahu, addressing a joint session of the U.S. congress in July as protestors marched outside, reminded his Yankee benefactors:

These protestors chant, “From the river to the sea,” but many don’t have a clue what river and what sea they’re talking about! They not only get an F in geography, they get an F in history! They call Israel—they call Israel a “colonialist” state? Don’t they know that the land of Israel is where Abraham, Isaac and Jacob prayed; where Isaiah and Jeremiah preached; and where David and Solomon ruled?

For nearly 4,000 years, the land of Israel has been the homeland of the Jewish people. It’s always been our home; it will always be our home!

What does it mean, then, for the land to belong to the Jews? For many, the story that a god once promised to Jews the land between the Nile and the Euphrates, or the belief that a Jewish ingathering is a prerequisite to Armageddon, is all there really is to it. David Grün, rené Ben-Gurion, who led the zionist secession and ethnic cleansing in Palestine and became the new state’s first prime minister, put the case succinctly: “It is the Bible that is our mandate.” In secular versions of this argument, it’s the Jewish people’s “historical roots” in Palestine—rather than some mythical promise to a patriarch by a deity in the bronze age—that matter most; the bible is simply the receipt. Ben-Gurion, to his credit, knew what sort of protest this would invite, and how it might sound to outsiders:

One side [the Arabs] says: ‘We have been living here, not for a matter of days or months, but for 1,400 years. Our fathers and forefathers are buried here. Grant us liberty to live as we please, give us a democratic government, let us be ruled by elected representatives, as you are. Why should you strangers govern us from afar?’ These arguments [the British] will understand because they are straightforward, because of their elementary appeal.

The other side is the Jewish people, with a genealogy of 3,500 years, the Bible as its sacrosanct title-deed to Palestine, and a promise from the British Government….

It is all very confusing.

To say the least. It is confusing, above all, that history honored one and not the other. And it is history, as it goes, that is at stake in the dispute, just as much as, if not more than, is the land. But whose history? On the website of the Israeli foreign ministry, in a section titled “Facts about Israel” (sic), one finds the incredible assertion that

Jewish history began about 4,000 years ago (c. 17th century BCE) with the patriarchs—Abraham, his son Isaac, and grandson Jacob…. The Book of Genesis relates how Abraham was summoned from Ur of the Chaldeans to Canaan to bring about the formation of a people with belief in the One God.

One can, for the sake of argument, ignore the obvious problems of taking biblical tales and figures as factual ones, and go along with the story. One may believe these legends correspond to the people living in bronze age Palestine, to whom the modern Jewish people trace their ancestry. One might even agree that the specific periods of biblical significance, from the bronze age till the Roman era, matter more than any other times of Palestinian habitation in establishing who now should claim the land as theirs. One can accept all this and more and still the question remains: What makes that history Jewish history? What makes the legacy of the Levant’s ancient inhabitants a specifically Jewish birthright, in a way it isn’t also that of the Samaritans, the Mandaeans, the Druze, the Syrians, Lebanese, Jordanians, Egyptians and, of course, the Palestinians? What makes the land definable by a single branch of a larger tree, whose roots are buried in the soil of still more living trees?

A tendentious framing of history is what continues to shape public attitudes on the “Arab-Jewish question”—a question which, when it isn’t spun in terms of a religious conflict, is cast as an intractable ethnic one. This corrupts how one regards not just the “root causes” of the conflict, but even more than that, the outlook of what a just solution might be. It’s seen as natural to pit “Jews” and “Arabs” as essentially distinct groups, discrete and oppositional, and forever at war (as Joseph Biden tells it) thanks to the Arabs’ “ancient hatred of Jews.” It’s taken for granted to view the country in terms of an ancient patrimony, belonging to a modern ethnic claimant, and that it makes sense to award (or divide) the land as such. This leads to some bizarre lines of argumentation, like the claim that zionism can’t be “colonial” because Jews were indigenous “first.” Even defenders of the Palestinian cause find themselves backed into the premise, and having to quibble with the meaning of “indigeneity.” It also underwrites the assumption that Jews will never be safe unless they have an ethno-state of their own, as the good book says they had in days of yore; and it validates the suggestion that, with all the other “Arab land” around, the Palestinians ought better to renounce their claims, accept their crumbs, maybe pack their luggages after all. It is more than a piece of historical trivia. It is, in fact, a historical travesty, and an injustice to history, and so long as it reinforces a historical injustice, it is a healthy heaping of injury onto insult.

What makes the land definable by a single branch of a larger tree, whose roots are buried in the soil of still more living trees?

There’s a version of this history you likely already know. It’s what’s taught at Sunday school and Hebrew school, in textbooks and in classrooms, in undergraduate lecture halls and other sites of rote and mundane learning. If only by cultural osmosis, this is the version that most westerners, both religious and irreligious, in some form or another, probably picked up. The contours of that story should be familiar to most, even if the particulars are not; but it’s the particulars here that matter, and which are worth revisiting. The story goes, in so many words, like this.

It starts some time in the middle bronze age with a guy called Abraham, the “patriarch,” an immigrant from Babylonia who packs his wife and slaves and concubines and moves to the western Mediterranean seaboard to have lots of sons. There Abram (the suffix –ham is not yet appended, till Abram puts his foreskin in the game for an offer by a god he can’t refuse) finds the land inhabited by other people, but it won’t be for very long—the god has deeded the land as property, in perpetuity, to Abram’s offspring. Abram’s first-born Ishmael gets the short stick and has to settle for Arabia, but the real prize goes to the younger Isaac, whose progeny will be called “the sons of Israel” and dwell in the land of Canaʿan. A brief excursion into Egypt leads to a bad break for the Israelites and a few hundred years of slavery, toiling on the pyramids until Moses comes along to lead them out on a very scenic route into the wilderness. The god of Abraham, El Shaddai, whose secret identity is “Yahweh,” gives Moses the famous list of shalts and shan’ts that form the Israelite religion, the foremost rule being to worship Yahweh only. They bring their new faith back with them to Canaʿan, proceed to quarrel with the neighbors, then take the spoils of land for a genocide well done.

By the 11th century b.c., the newly settled Israelites get a king of their own called David, a capital city in Jerusalem, and a sacred temple on the adjacent hill of Zion. At its peak, this magnificent Davidic kingdom stretches well across the middle east, from the Nile to the Euphrates, but troubles fall and split the monarchy in two. The northern half of the kingdom, “Israel,” which kept the name from the divorce, is conquered in the 8th century by the Assyrians, who exile the people off the land and out of history. The southern kingdom, “Judah,” which got to keep the capital, falls two centuries later to the hated Babylonians, who trash the temple and take the Jews into captivity.

Thus the land is emptied, and left to be repopulated with foreigners. Some of these new aliens, living in what used to be the northern capital Samaria, will come down to us in legend as the “Samaritans.” As for the seed of father Abraham, only the southern Jews of Judah survive; and only when the Achaemenids conquer Babylon in the late 6th century b.c. does the good king Cyrus bring the exiled tribe back home. A second temple is erected in Jerusalem, where the Jews, having learned the hard-knock lesson that there is no place like Zion, buckle down to take their torah seriously. But the ancient laws are once again at risk in the 2nd century, when Persian rule falls to the Greeks, and Jerusalem’s new management veers awfully near to the ways of Athens. So pious terrorists led by Judah “the Hammer” Maccabee rise up against the diabolical forces of hellenization, and after a well-known bit with a menorah, take back the holy land for Yahweh, converting everyone inside it into Jews. Their short-lived kingdom, or theocracy, ruled by the priest-kings of the Hasmonean dynasty, is absorbed soon after by the Romans. (Here is when a rowdy carpenter is crucified for treason.) In the 1st century a.d., an anti-Roman revolt results in the razing of Jerusalem, and after a botched rematch in the 2nd, Jews are banned from the holy city, Judaea is rebranded “Syria-Palaestina,” and the chosen tribe is exiled once more…

This narrative was taken more or less as factual, if not literal, for most of literate western history, having been spun out of the cloth of the word of god. It is the bible’s story, in other words, and perhaps until Baruch Spinoza in the 17th century a.d., the basic truthfulness of scripture was hardly doubted. In the 19th century, German scholars of what was called the school of “higher criticism,” like Wilhelm de Wette and Julius Wellhausen, ruffled not a few religious feathers by treating the bible less as a record of the times when it was set, than of the times when it was written; an evolving record, too, which bore its authors’ changing ideologies and agendas. But these early critical scholars were also products of their times, and seemed awfully keen to posit that the stuffy, rootless Jew in the Christian west’s imagination was a degraded form of an older “national” Israel, whom the Christian god had chosen after all. Nor could they quite repress the age-old habit of taking the biblical chronology at its word. Even those with a less confessional or apologetical intent have a tendency merely to “paraphrase” the bible, shaving off the supernatural bits and accounting for creative liberties, combing through the text for a residuum of truth.

One might do better combing through the dirt. For a time the archaeologists—led by the American orientalist William Albright and his student, the theologian George Wright—supplied a pious counterweight to the more skeptical takes by Europeans. With a spade in one hand and a bible in the other, these “biblical archaeologists” thought material digs might prove the good book’s “essential historicity.” (To this day Albright, who was in life a committed evangelical Christian zionist, lends his name to an institute of biblical archaeology based in occupied east Jerusalem.) This wishful enterprise was challenged, and eventually discredited if not abandoned, with the appearance of critical works by Thomas Thompson and John Van Seters. After many hems and haws, and apart from die-hard fundamentalists, most scholars came around to the once-contested view that the “patriarchal” account of Israel’s pre-history was folklore.

Other cherished stories fared no better. The Egyptian slavery and exodus imploded under evidential scrutiny, as did the Hebrew conquest and settlement of Canaʿan. The so-called Israelites, it turned out, had been right there, all along, among the pagan locals—if it made sense to distinguish the two at all. Even so, the bible’s partisans kept the faith that even if the bronze age legends were collapsing, there at least was a Davidic kingdom in the iron age, long-lost but always longed-for, a precedent by which to stake the land as “theirs.” This fantasy was put to test and laid to rest by none other than modern Israeli archaeologists, associated largely with Tel Aviv University, who showed there never was a “great united monarchy” with its capital in Jerusalem, and that king David—if he was real—was just a local chief or petty warlord collecting rent in the southern hills. Further investigations unearthed no signs of any mass exile and return, either.

What is left of Israel’s ancient history? Increasingly, not much. A tremendous stride was made toward clarity with the 1992 publication of In Search of Ancient Israel, by the late professor Philip Davies, who showed there were three possible “Israels” people typically mixed up. There is the “biblical Israel,” a figment of mythology and theology, which only exists in scripture. There is the “ancient Israel,” a construct or reconstruction dreamed up by the scholars. And there is the “historical Israel,” the actual entity or entities referred to in antiquity by that name in the land between the Mediterranean and the Jordan. What Philip Davies helped expose is that the second one had been based largely on the first, in ways no other field of history would deem normal; and neither the second nor the first had very much to do, if anything, with the third.

One can appreciate all these developments in modern history and criticism and archaeology and still pose the rebuttal: so what? Ben-Gurion staked his claim on Zion not based on any scriptural or religious fine point, but on the simpler and more sensible fact that Palestine had been the homeland of his ancestors. A people who, through a litany of empires and banishments and existential catastrophes, in endless conflict with foreign enemies, managed to keep their essential ancient character, and cling to a land that was always theirs. Whatever battles were or weren’t fought, and whichever kingdoms may have existed or did not, surely no one can dispute the land had been the setting of a long, continuous history that was, distinctively, a Jewish one.

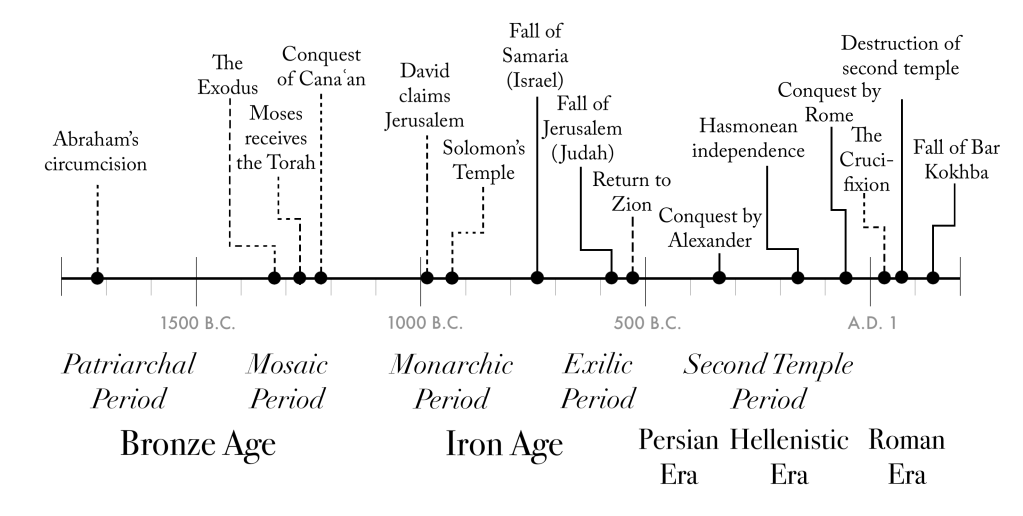

This is conventional wisdom, at present. Does it hold up? In 2022, the archaeologist Yonatan Adler published his paradigm-smashing findings on Jewish history in The Origins of Judaism. In his research Mr. Adler—a professor at Ariel University, located in an illegal Israeli settlement in the occupied west bank, whom no one can accuse of trying to delegitimize the Jewish people—found the earliest evidence of Judaic practice among the people living in ancient Palestine. He has done so not by asking what the priests and kings and scribes were up to, according to biased texts, but by looking at what the common folks were actually doing. The archaeological data places the very start of a culture recognizable as “Jewish” in the region’s Hasmonean era. That is to say, if there’s a beginning to a people or a society living a distinctly and identifiably “Jewish” way of life to be found in the material record, it’s as far late as the 2nd century—near the end of the biblical narrative, only a hundred-something years before the time of Christ.

Thus says the lord Yahweh unto Jerusalem, Your ancestry and your birth is of the land of Canaʿan; your father was an Amorite, and your mother a Hittite.

Ezekiel 16:3

But of the cities of those peoples, which Yahweh Elohim is giving to you for inheritance, do not leave alive anything that breathes. But utterly destroy them; exterminate the Hittite, and the Amorite, and the Canaanite, and the Perizzite, and the Hivite, and the Jebusite, as Yahweh Elohim has commanded you.

Deuteronomy 20:16-17

What would it mean to see Judaic culture as something new in the Levant in the time of the Hasmoneans, right before the turn of the Christian era? It means, for one, that the standard Hanukkah tale of pious Maccabee guerrillas, who “restored” the ancient laws from hellenistic degradation, isn’t exactly quite right. To 2nd century b.c. Levantines, the religion of Mosaic law and torah observance was itself the innovation, something their ancestors were simply not a part of. For another, it means the conventional account of the land’s distinctly “Jewish” past begins a millennium or two after what is assumed. Per tradition, the Jews were exiled from their land in a.d. 70, when Zion’s temple was destroyed, or in 135, when the Romans quashed the uprising of Simon bar Kokhba. This means, in turn, that when we refer to an ancient past in which the land of Palestine was substantially Jewish, we’re only talking about around a couple centuries.

That isn’t to say they weren’t living there, either after or before. Yehudim resided in Yehudah, or Judaea, the southern hinterland around Jerusalem, well before a thing called “Judaism” existed. And the widespread notion that Jews were exiled, en masse or in toto, after the bar Kokhba fiasco—as implied in the Israeli declaration of independence, as well as the national anthem—is a myth. The truth is that most Roman Judaeans stayed where they were. (In fact, the generations immediately after the alleged “exile,” when the rabbi Yehudah ha-Nasi compiled the mishnah in Galilee, are called the “Jewish golden age” in Roman Palestine.) There is no question that Jewish people can trace their culture or their ancestry back to ancient occupants of southern Syria. The question, rather, is whether it makes sense to call those ancient peoples “Jewish,” or to think it’s only Jews who are their progeny.

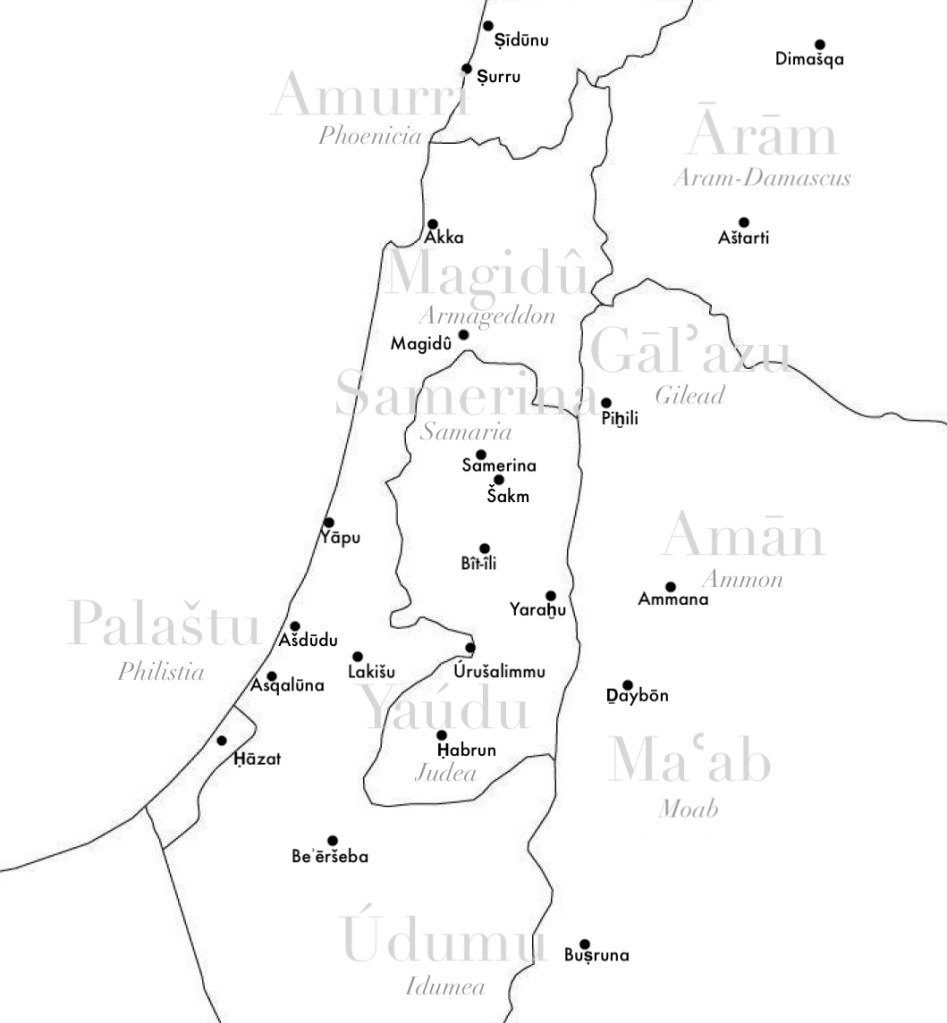

The conventional answer to the question comes from an ethnocentric framing, and the ethnic frame is taken from the bible. It says the history of Palestine is that of a people called “Israel,” marked by distinctive cultural practices and belief in a single god and in continuous descent to modern Jews. Despite the long and sweaty labors of the archaeologists, barely a handful of odd references to any entity called “Israel,” severely few and certifiably far between, has been exhumed. The closest match to the bible’s version comes from a 9th century b.c. stone slab, inscribed in the name of a king of Moʿab, in what is now the Hashemite kingdom of Jordan. Written in the Phoenician script, using what is called a Canaanite tongue, the tablet tells of a neighboring kingdom called Ysrʾl ruled by ʿmry and his son, who seem to have worshipped a patron deity called Yhwh. Assyrian records refer to the same as Bīt Ḫûmrî, or “house of Omri,” a petty iron age kingdom based in the central highlands of Šomron, or Samaria, which is where the bible sets its “northern kingdom.” Here is what the archaeologist Israel Finkelstein identified as “the first true, great Israelite state.” But this Bīt Ḫûmrî—or “Israel,” if you like—had very little to do with the southern hill country Yaúdu or its city Úrušalimmu. When the Assyrians annexed Samaria as the province Samerina, the majority of the land’s people stayed put.

To the south, the younger and smaller inland kingdom of Yaúdu had a history of its own. It was never unified under a single monarch with its more prosperous neighbor in Samaria—let alone furnished the capital—nor is there any record of it going by “Israel.” Through the Persian era, the central city Shamerayin looks to have done well for itself as an administrative center, while southern Yirushlem, after Babylon, lay in ruins. Yet despite an initial decline in Yehud’s provincial population, especially near the ravaged city, the archaeological record does attest to a general continuity. This land was never emptied by Nebuchadnezzar, nor was there a great replenishment under Cyrus. Its western neighbors, in comparison, thrived in the bustle of a Mediterranean coast. Only in the hellenistic period did Ierousalēm become a city again worth mentioning, and Ioudaía a dominant regional fixture.

Culturally, southern Syria in antiquity was beautifully heterogenous. It would be anachronistic to project into the region’s past a particular ethnic unity like “Israelite,” or “Jewish.” The upper Galilee, in the north, had more in common with Phoenicia, in modern Syria and Lebanon, than with either the Samarian or Judaean highlands. The northern coast likewise shared a Phoenician affinity, while along the coastal south, a hybrid culture of both indigenous and Mycenaean provenance was left in the rubble of Philistia. Judaeans were a minority. They seem to have had much fluidity with the Edomites or Idumaeans, their transjordanian southern neighbors, and both were plugged into a broader trade and cultural network with Egypt and Arabia. Though differing in dialect, a common Semitic language, along with shifting, porous borders (if it makes sense to speak of “borders” in antiquity at all) meant that mixing and migration were the norm. The arrival of the great empires, as well as local reconfigurations, would bring an assortment of new languages and customs and cultic practices and laws into a region whose makeup was anything but fixed.

It would be anachronistic to project into the region’s past a particular ethnic unity like “Israelite,” or “Jewish.”

In the oldest attestations, words like “Jewish” or “Judaean” were geographic, referring to the southern highlands or environs. Later, the word attached to a people, with Yāḫūdāya living in Babylonia, and Yehudaye on the Egyptian isle of Elephantine. These same Judaeans of Elephantine identified, in other contexts, as “Arameans.” But until late in the game, Judaeans didn’t seem to refer to themselves as “Israelites.” And yet there were a Levantine people known as Israælitai, on the Greek island of Delos, who hailed not from Judaea, but from Samaria. These are ethnical conundrums. The 5th century b.c. Greek historian Heródotos, maybe the earliest adopter of ethnic studies, wasn’t too hung up on the specifics. He called them all just “the Phoenicians and the Syrians of Palestine.”

We now know quite a bit about the holy land’s religious promiscuity. The deity Yw (Yā-ô) or Yhw (Yāhû) was something of a local favorite, but so were the Canaanite storm god Bʿl (Baʿal) and the Canaanite bull god ʾl (El). The latter two are well-attested in the bronze age Syrian literature of Ugarit, which give a rare and colorful glimpse into the gods who didn’t make the bible’s cut. The cult of Yhwh, however, seems to have come from the south, very plausibly imported from Arabia, with early appearances in Sinai and Edom. Far from the one true abstract god of “serious” theology, this god had a body, and a wife, and made his home in a cosmology that was thoroughly congested. Monotheism would have to wait until much later (and likely not before Islam). In the texts that became our holy bible, El becomes the alias of Yahweh, who’s depicted with the attributes of Baʿal, and the Canaanite goddess Asherat is reduced to a pagan idol which the Israelites keep on needing a reminder not to pray to. But up through the Persian period, the Judaeans of Elephantine were worshipping Yāhô in their officially sanctioned temple, with a host of other deities besides. And they were doing so as contemporaries of the “second temple” priesthood—who, tradition tells us, should have known better—with their apparent license, if not guidance. The acolytes of Zion missed the memo about Moses, and they didn’t know of any “torah,” either.

Looking out onto this pluriform and variegated picture, one gets an unmistakable impression. Who exactly were these “Israelites”—this highland people who spoke the language and worshipped the many gods and shared the cultures of their lowland neighbors in the land known to us otherwise as Canaʿan? They were Canaanites. At least, it wouldn’t make sense to say they weren’t, except the bible tells us so. But to call them all “the Canaanites” may be to repeat the blunder. The so-called Canaanites, as the bible scholar Niels Lemche argued, were “not a real nation but an imagined nation placed in opposition to the Israelites.” What the diverse and multifaceted peoples lumped together as “the Canaanites” really held in common was the role allotted to them in the bible. They are “the ‘bad guys,’ hated by God and the world, doomed, and to be replaced by the Israelites.”

And yet the actual Israel of history is scarcely known. It cropped up briefly in the central Samarian hill country, near the city now called Nablus, just one small kingdom among many on the altogether pagan landscape of the Levant. In the 8th century b.c., Samaria became part of Assyria and Israel was no more. Then for the next 800 years, as far as archaeology is concerned, “Israel” as a place or polity was unheard of. Not until the 1st century a.d. did Ysrʾl reemerge, as a name inscribed on local coinage minted by independence-seeking rebels in their failed struggle against Rome. At this point, the word is doing something different. This time, the term is linked not with central Samaria, but with southern Jerusalem. It’s been adopted by the people called Ioudaïos. It’s been transformed, far from its humble iron age beginnings, into the splendid Israel of legend, an Israel with a mythic past that reaches back to time immemorial, where Palestine was always Israel’s, and Israel means the Jews. There is very little room in this legend for the land’s other diverse occupants—except to be removed—nor for its peoples’ decidedly unkosher cultural habits—except to be shunned as sin. Instead, it’s only the religious innovations and national myths of a single, late-coming group that come to stand for, and stand over, all the rest. As for the sundry others, their own histories are lost, their testimonies muted, their contributions spurned or relegated to the raw materials of what will be remembered simply as the Jewish people, buried in the soil of someone else’s promised land.

Nineteen centuries needed to pass before that old pipe dream of a “Jewish state” was bodied forth into reality, midwifed by the “defense army of Israel.” To this modern incarnation, the state called “Israel” has affixed a further adjective—Jewish and democratic—a formula which its figureheads waste no chance to bring up, with often baffling results. In July’s congressional address, for instance, Mr. Netanyahu boasted:

The men and women of the I.D.F. come from every corner of Israeli society, every ethnicity, every color, every creed, left and right, religious and secular. All are imbued with the indomitable spirit of the Maccabees, the legendary Jewish warriors of antiquity.

One would think the Maccabee rebels were driven by a spirit of multiculturalism. One would be wrong. As the journalist Christopher Hitchens once remarked, “it was nothing remotely multicultural” that got the Maccabee insurgents so riled up. In the deuterocanonical book of Maccabees, it all starts when their father, Mattityahu, witnesses a fellow Jew perform a hellenistic ritual, and gets so moist and livid he kills the offender on the spot. (The author of i Maccabees compares Mattityahu favorably to Phinehas, a biblical priest who slays a fellow Israelite for sleeping with a gentile.) The wicked Seleukid king Antiochos, you see, has turned Jerusalem into a Greek-style polis, encouraging foreign ways and stopping Jews from keeping torah. What follows is a theocratic insurgency, led by the brothers Maccabee, of ethnic cleansing, forced conversion and coerced foreskin removal on their way to transform Palestine into an independent, and homogenous, state of Jews.

Of course Judaeans, like everyone else in west Asian antiquity, were worshipping foreign deities from the start, and the influence of Hellenismós wouldn’t have been necessarily unwelcome. The well-trod trope that pits “Athens” against “Jerusalem,” as cultural or philosophical opposites, is wildly overblown. (Newer research, in particular by Philippe Wajdenbaum and Russell Gmirkin, makes a compelling case for seeing a hellenistic provenance to the bible.) Jerusalem, in fact, was until then a sparsely populated hinterland, as shown by the findings of the Israeli archaeologist Oded Lipschits; it’s only when the Greeks refurbished it that it became a city again at all. Nor were the Seleukids known to suppress the religions of their subjects. And if Yonatan Adler is correct about the “origins” of Judaism, in the reign of Antiochos, there was no culture based on torah yet to outlaw.

In all probability, the real cause of the Maccabean crisis was rather more mundane. According to the historian Sylvie Honigman, the catalyst of the uprising was taxes, not theology; to the classicist John Ma, the whole episode was an administrative affair. But theology was the language of ancient politics. Whichever way it went, the convulsions of Greek decline had left a gap filled gleefully by the Hasmonean upstarts, who managed to secure imperial sponsorship as the local ruling family, and made the pious “Maccabees” their founding myth. The Hasmonean dynasty took Judaea and expanded, annexing territory from the south in Idumaea, across the Jordan in Nabataea, from the plains and port cities along the coast, up through Samaria and northward, near Aram and Phoenicia. Here, in the 2nd century b.c., was the very first time this eastern slice of the Mediterranean world came under the rule of the unassuming Judaean hills. A new official ideology was promoted, coined in ii Maccabees, and modeled as a counter-movement to the Hellenismós of the Greeks—Ioudaïsmós, the first appearance of something called “Judaism.”

A central plank of “Judaist” state-building was the enforcement of the torah, which up till then was basically unknown. The land’s inhabitants were polyglot and polytheistic, and its material cultures, documented by the archaeologist Andrea Berlin, were impressively cosmopolitan. In the Hasmonean period, something changed. The diverse regions of southern Syria, which had never formed a coherent unity, were brought together under the thumb of priests from backwater Jerusalem. A cosmopolitan culture, reflecting Palestine’s position on the Mediterranean seaboard, was replaced by the plainer, more parochial culture of the inland hills. For the first time in its history, the system of prescriptions and proscriptions spelled out by the legendary lawman Moses enjoyed something like popular observance, outside whatever scribal nobodies were behind it, and the torah became more than a rarefied concern. The “Judaization” of Palestine wasn’t only the attempt to make the rest of the country “like Judaea.” It was what made the Judaean masses “Jewish” to begin with.

Here, in the 2nd century B.C., was the very first time this eastern slice of the Mediterranean world came under the rule of the unassuming Judaean hills.

What this meant was something new: a codified form of Yahweh-worship, unique in its insistence on theistic exclusivity, with a singular attachment to Jerusalem. It also meant the invention, or reinterpretation, of the old. The torah of Moses was presented as the ancestral law which everyone was, or should have been, obeying since the bronze age. The Hasmoneans conquered other territories which, as they alleged, were really their inheritance all along. As far as we know, the Hasmonean family only styled themselves the rulers of the Judaeans, and their kingdom was called Judaea. But in their written propaganda, as comes down to us in holy books, their patrimony was the biblical “Israel.”

The experts differ on how and why Judaeans from the south came to identify with the name of an iron age Samarian kingdom. The archaeologist Navad Na’aman is likely right that Bīt Ḫûmrî, having been the far more consequential kingdom, was simply more prestigious, inducing later Judaeans to trace their lineage back to a “glorious unified past,” adopting Israel’s heritage as their own, whether or not the link was true. Many people and communities have claimed a questionable descent from the elusive biblical Israel; as the scholar Andrew Tobolowsky argued, the Judaeans’ claim is hardly different. But their appropriation of the label did put them at odds with another people claiming to be “Israelites,” whose claim was just as good or even better, and who’d been living in the former territory of the historical real-world Israel: the people called Samaritans, from Samaria.

Some time in the 2nd century b.c., members of this community left their imprint in the Aegean, on Delos, where they described themselves in Greek as “Israælitai who make first-fruit offerings to the temple of Ar-garizeín.” Mount Gerizim, near the old Samarian city Shechem, had been for centuries the site of one of Yahweh’s sanctuaries, and given Samaria’s size and stature, probably the biggest one. It was to Gerizim, not to Zion, that these Israelites paid their dues—and there’d been other shrines besides, from Galilee in the north down south in Egypt and even Libya. But by the century’s end, this era of relative pluralism and coexistence, if not mutualism and cooperation, came squealing to a halt when Yohanan Hurkanós, or John Hyrcanus, the Hasmonean king and priest, marched into Samaria and laid waste its cities and its temple. Their competition dealt with, Jerusalem took the title as the only game in town. Their temple could become the exclusive site of national tax collection and a centralized official cult. And the devotees of Zion would be remembered as the sole legitimate claimants to a land deed granted, as their book tells it, by their god.

“You have devastated their territory, you have done great damage in the land, and you have taken possession of many places in my kingdom.”

“We have neither taken foreign land nor seized foreign property, but only the inheritance of our ancestors, which at one time had been unjustly taken by our enemies. Now that we have the opportunity, we are firmly holding the inheritance of our ancestors.”

1 Maccabees 15:29, 33-34

The Samaritans, as it happens, are still kicking. Numbering fewer than 1,000, the small community of Shomronim have resided in or near the Palestinian city Nablus, in the shadow of their holy ruins on Gerizim, for millennia. They practice their own torah, based on their own version of the pentateuch, which is nearly identical with the Jewish one but for two telling exceptions. The Samaritan text names Gerizim explicitly as Yahweh’s sacred abode (on this, the Jewish pentateuch is silent), and it is written with an earlier Canaanite script (unlike the imperial Aramaic of the Jews). Per Jewish tradition, the Samaritans got their start as schismatic or fraudulent Jews, who rejected Zion to do their liturgy on the wrong hill. If you ask the Samaritans, it’s the Jews who split from them. To most of everyone else, the Samaritans’ existence barely registers, apart from the Christian parable which makes it seem significant that a Samaritan, one time, was “good.” The orthodox rabbinate of modern Israel regards Samaritans no better, and maybe worse, than any gentile people. As for the Samaritans themselves, they are, and always were, simply “Israelites.”

Since 1994, a ruling by the high court in the state of Israel has made Samaritans something like honorary (if naughty) Jews, at least for the purposes of immigration and citizenship, based on the controversial Jewish “right of return.” The law, permitting each and any Jew to “return” to Israel from “exile,” was held to apply to a people who aren’t Jewish, and who’d never even left. As misunderstandings go, this was an improvement on what came before. In the Jewish bible, the northern monarchy is said to be whisked away by the Assyrians, lost forevermore (at least until a messianic kingdom come), and the population is replaced by gentiles pretending to be Israelites. These, the legend goes, are the Samaritans. And yet imperial deportations, though they happened, were rather limited, often displacing local elites but leaving commoners where they were. But it’s the ruling class whose stories get to be written down, and whose identities tend to be remembered. It is perhaps a function of the elitism of textual traditions, conflating rulers with their peoples, that the Samaritans went down in history as strangers in their own home.

There are, in fact, good reasons to believe the Samaritans were the original authors of what became the torah, or were a major part in a shared invention of it with Judaeans. And the Elephantine records attest to a sort of kinship or compatibility among the cultic sites of Yahweh-worship that transcended regional lines. But the downfall of Samaria’s ruling family in 722 b.c., and the toppling of Jerusalem’s in 586, provided a theological teaching moment that became a political one for later rivalries. In the prophetic discourses of the bible, these defeats are rationalized as divine punishment, and the state of being conquered is theologized as “exile.” The prophets’ hysterical (and downright pornographic) polemics credit the almighty’s wrath to the people’s whoredom and infidelity, by which they mean the people’s acting like the goys. Having forsook the laws which made them Yahweh’s favorite, the faithless ingrates are only getting what they asked for, in being sent to “dwell among the gentiles.” They lose what made their nation “sacred,” or set apart.

These are the ideological motifs of a nationalist agenda. It’s the same kind of national chauvinism that undergirds the deity’s exhortation to Joshua to exterminate their Canaanite neighbors, on the grounds that goyish ways might rub off on the chosen tribe. And when inevitably they do, the punishment of Israel and Judah is a reversal of their national founding: they’re driven back into the wilderness, back to “Egypt.” Here it’s worth remembering that the Hebrews weren’t literal slaves in bronze age Egypt, but southern Syria was under Egyptian rule. During the “exile,” so-called, the promised land was not quite emptied, though in the scripture’s propaganda, it is spiritually so. The land itself becomes the desert, barren and profaned, but still very much inhabited—by the “wrong” sort. The good book calls these people ʿam haʾaretz, “the people of the land,” a mix of pesky gentiles and mongrelizing natives. (In the mishnah, the same term is deployed to refer to unkosher ignoramuses, wayward Jews whom true-believers should avoid.) The exile, as a collective mass experience, was not literal, but theological and political: a metaphor of illegitimate rule and social order. In the bible’s sectarian telling, Samaria’s loss of sovereignty is blamed on their cosmopolitanism, and their leadership’s replacement by Assyrian governors is the natural result. Impious Samaria is said to be carried off among the nations, and replaced by foreign immigrants, which are two ways of hammering home the point: they are now goys. The Judaeans are scattered, too, but make it back to god—the only ones who make it back out from the desert.

This trope of ruin and renewal bolstered Judaeans’ claims of national exceptionality, and made their case for being Israel’s true successor. The narrative is cyclical, inscribing Israel’s mythic history as their own. Just as Egypt is mirrored in the Babylonian captivity, Cyrus becomes a sort of second Moses who leads them home. The founding prophet Joshua is doubled in a later biblical Joshua, the priest who founds the second temple. The Seleukids’ mischief in Jerusalem, followed by the Maccabees’ temple-reclamation, reproduce this theme in miniature; and as the temple must be “purified” after foreign contamination, so too should the land, a point on which the ethnic-cleansers Joshua and John Hyrcanus coincide.

When the Hasmoneans took Jerusalem and conquered Palestine for Judaea, these myths supplied a legitimizing basis for regime change. After Jerusalem fell to Rome in a.d. 70, the loss could be seen as yet another episode in a readymade motif. The self-perception of being exiled again was one way for the Judaean ruling class to process humiliation, and to cope with foreign rule, even if the majority of their people stayed in their homes. Later on, over the centuries, more Judaeans took off voluntarily, as peoples tend to do, joining a robust diaspora which had already dwarfed the homeland’s population by the Greco-Roman eras. For some, the destruction of the temple spelled the end of the national question and its revival (or better yet, its resurrection) in a new Joshua, or “Jesus,” and his messianic church. For others, the end of cultic practice and ethnic self-rule forced a reckoning toward new rabbinical readings of the torah, ones which only took on a familiar form in a diasporic existence, where a spiritual exile would be felt increasingly as literal.

But “Judaean” was just one identity assumed in southern Syrian antiquity, and “Judaism” only a single -ism. There were more. There were the Samaritans, fellow keepers of the torah, a group whose past is Israelite but isn’t Jewish. There were the Christians, believers in a new Yeshua and a new Israel, with a liturgy patched up alongside their rabbinical neighbors by the ruins of a sacrificial temple, whose obliteration both sects were the efforts to make sense of. There were the Mandaeans or Sabians, who trace their lineage to the old pre-Christian followers of Yohanan the baptizer. Outside the Mosaic traditions, the more traditional forms of “paganism” lingered, as did the earlier, polytheistic sorts of Yahweh’s veneration, which mixed and blurred with the gods of the Greeks and Romans, as they had done with other cultures’ gods before; or merging with the syncretic cult of theos hypsistos, “the most high god” of many names in the Greco-Roman world. All of these are weaves in the region’s cultural tapestry, the heritage of peoples constantly in flux. These people, whose history is laid out succinctly by the theologian Mitri Raheb,

changed their language from Palestinian and Phoenician West Semitic to Aramaic and Hebrew and later to Greek and Arabic. Their identity shifted from Canaanite and Philistine to Judahite/Israelite, to Hasmonaic, to Roman, to Byzantine, to Arab, to Ottoman and Palestinian, just to name a few. They changed religion from Ba’al to Yahweh. Later they believed in Jesus as the Christ and became Christians, who were first Aramaic-speaking monophysites, before being forced to become, for example, Greek Orthodox. Obligated to pay extra taxes during Islamic dominance, they became Muslims. And yet, throughout the centuries, they maintained a dynamic and flexible identity.

These are the am ha’aretz, the ones still on the land, who’ve been living in the south Levant through its successive kingdoms and empires, its triumphs and catastrophes, invasions and migrations, adapting and resisting over millennia. They are, in a simple word, the Palestinians.

Remember, O Yahweh, what has befallen us; look, and see our disgrace! Our inheritance has been turned over to strangers, our homes to aliens.

Lamentations 5:1-2

It is an irony of biblical proportions that this people of the land were blotted out, in popular memory, from what the zionists so breezily called a “land without a people.” In the western imagination, the Jewish settlers of the late 19th and 20th centuries arrived to find the place in shambles, mismanaged by the paltry smattering of pagan nomads and heathen boors in a desert waiting to be bloomed. This fictive terra nullius looks straight from the bible, with the am ha’aretz on borrowed land vacated of its exiled owners. Somehow or another, the inconvenient presence of 1.4 million gentiles in the “Jewish homeland” on the eve of zionist statehood needed to be accounted. In the famous libels of Joan Peters, the Arab majority were chalked up to recent waves of illegal immigration, solely drawn to Palestine to cash in on the blessings Jews had brought; others grant that Arab habitation was continuous, but only after the Muslim conquerers arrived. Once again the common people were conflated with their rulers, and the Palestinians, to a large degree the heirs of all who’ve lived there since the biblical times and earlier, were believed to be imported from Arabia, replacements of the rightful occupants who, though not quite “exiled,” had understood themselves as so. This irony was redoubled when the zionists, who defined their movement as the “negation of the exile,” bought their dream at the cost of driving 750,000 native Levantines into an exile of their own.

The ironies only compounded with interest. The dismemberment of Palestine resulted in the founding of a “Jewish state” whose name is taken not from Judaea, but from Samaria. That state encompasses the coast and plains and desert held by biblical Israel’s enemies—the Canaanites and Edomites and Philistines—while both Samaria and Judaea make up the west bank territory of the occupied non-Jewish rump. The maintenance of the zionist enterprise, which always insisted on its Levantine rootedness, has relied on western Christian empires as its guarantor, and guaranteed a confrontation with the east—an east which Vladimir Jabotinsky, the political ancestor of the reigning Likud party, derided as “a yelling rabble dressed up in savage-painted rags.” His frenemy on the zionist “left,” David Ben-Gurion, minced no words either:

We are in duty bound to fight against the spirit of the Levant, which corrupts individuals and societies, and preserve the authentic Jewish values as they crystallized in the [European] Diaspora.

The zionist luminary Theodor Herzl, who admired Cecil Rhodes and praised the British for “cleaning up the Orient,” hoped to build in Palestine “a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.” Zionist prejudice had as its object not only the Arab despots and fellahin, or native peasantry, but likewise the eastern Jews, thought to be just as primitive. And zionist opinion of the broader diaspora was also not too flattering, viewing the “ghetto Jew” as nebbish and pathetic, if not diseased and unassimilable. “Because the Yid,” wrote Jabotinsky, “is ugly, sickly and lacks decorum,

we shall endow the ideal image of the Hebrew with masculine beauty. The Yid is trodden upon and easily frightened and, therefore, the Hebrew ought to be proud and independent…. The Yid has accepted submission and, therefore, the Hebrew ought to learn how to command.

The concept of galut, or exile, had roots in early Judaic theology, but seeing diaspora as exile was a notion of the Christians, who thought the temple’s fall and Jews’ dispersal throughout Europe were punishment for killing Christ. The image of the cursed and wandering Jew would prove to be an indelible trope of old-school antisemitism. In yet a further irony, the zionists accepted the view of 19th century Germans that Jews in exile were a degenerate and deracinated form of the earlier monarchic Israel. But while the Germans believed that Israel was born again in (protestant) Christianity, the zionists placed hopes for redemption in a western nation-statehood. The “negation of the exile” meant the negation of most of Jewish history. It’s no wonder that Ben-Gurion, hoping to forge a canon for the young zionist entity, had little time for the ethics of the talmud, the wisdom of Maimonides, qabbalah’s mysteries or the Jewish socialist tradition. He skipped back 3,000 years to the myths of David and Joshua.

The book of Joshua, in particular—with its massacres and conquests, its land-grabs and annexations—was Ben-Gurion’s special passion, the subject of a private study group he convened for generals and politicians and intellectuals to workshop the new state’s destiny. It is in Joshua that one may find a blueprint for the zionist self-image: as a nation that, from its first step across the Jordan, is fully formed and set apart, alone against a hostile world, locked in perpetual war for national living space and survival. We know, of course, that none of it is true. We know the Canaanites were never liquidated by an invasive Hebrew army, and that “Hebrew” is a type of “Canaanite” (and both are written in Phoenician). The Levantines arranged and rearranged themselves in all sorts of identities, allegiances and boundaries, not always corresponding to what the bible or the British mandate or U.N. partition plan might draw. Among many other things, they became the iron age Israelites and Judahites, who in turn became many peoples more. Thanks to advances in genetic science, we know that modern Jews are related to ancient people in southern Syria. Genetically linked to Jews, but even nearer to their common bronze age ancestors, are the people called the modern Palestinians.

The land of Palestine was not always the property of a single people, and it was never the exclusive province of just one. Even when it was called the province of Iudaea, the “Jewish home” on the southern highlands was only one ingredient, sandwiched between the Samaritan and Idumaean homelands, and surrounded by Phoenicians and the Greeks. The historian Steve Mason pointed out that Jewish life within ancient Palestine was itself diasporic, if by “diaspora” one means a distribution of Jewish colonies or communities, living as minorities among gentiles, away from the mother polis in Judaea. Granted, even the bible can tell you that, depicting as it does a land that always was contested or commingled. But of the land’s ethnic pluralities, the scriptures call them “strangers,” and of their diverse cultic practices, the bible calls them “sin.” They are the detritus of a sacred history: corruptions of an idealized Jewish past, or impediments to an ideal Jewish future.

From the early days of modern Israel, Ben-Gurion praised the work of zionist archaeologists, like I.D.F. chief Yigael Yadin, in digging up the proof of the bible’s title deed, an effort which gained in 1967 new urgency and vigor. By 1969, the Palestinian archaeologist Dimitri Baramki complained of the field’s enduring “emphasis on the archaeology of the Old Testament period”—a brief slice of time, all things told—“at the expense of other periods unrelated to the Bible.” In the 1990s, Ghattas Sayej witnessed the bulldozing through 2,000 years of “unwanted” west bank history “to reach the ‘wanted layers’,” reflecting a bias whose effect is not simply academic, but also military. The discovery of Jewish facts in the ground become the basis for building new Jewish facts on the ground. Fearful of how archaeology was conscripted into the service of their dispossession, some Palestinians turned to vandalism or looting of antiquities. Others pitched a national counter-narrative, making a through-line back to the bible’s Canaanites and Philistines, replacing a Judeocentric story with an Arab-centric rebuttal.

Yet identity is a vague and slippery thing. The scholar Basem Ra’ad is right to point to Arabic as a “treasury” or a “storehouse” of northwest Semitic languages, and to Arab culture having Levantine continuities. These features’ origins are indigenous, not Arabian peninsular. Prior to zionist statehood, the ethnographer Lucjan Turkowski observed how the fellahin of Judaea, left in place through various regimes, preserved the customs and farming practices of their ancestors. Their “Arabization” was a gradual cultural process, not an ethnic mass replacement, taking shape as the beliefs and manners of urban elites trickled down to local commoners. Just as the Israelites and the Judahites, or the Samaritans and the Judaeans, emerged from other local “gentiles,” it was inevitable that they’d spawn off to other gens as well. Even Ben-Gurion, in a rare and fleeting moment of lucidity, thought early on that Palestinian fellahin descended from converted Jews. This assessment didn’t seem to figure in the zionists’ treatment of their cousins, even if in ways both cultural and genetic, the Arabs’ ancestral claims were stronger, though they’d taken different names and tongues and creeds.

I don’t mean here to say the case for Palestine is made by the Arabs’ being there first. The injustices past and present inflicted on the Palestinians are plain, without needing to wade in history’s weeds, for anyone with eyes to see. Nor is the point merely to contest the zionist claim to history, but rather how that falsified claim is done. This falsification of history dulls one to the severeness and the tragic ironies of the Palestinian catastrophe—of a people whose yearning for the land is rooted in the same mythic and distant past, so cherished by modern Jews, but with a longer and more recent continuity—and tends toward the racist devaluation of Arab life as fungible and rootless. It obscures how this mythology, like all nationalist mythologies, is a fiction, one that makes it seem like ethnic sovereignty and exclusivity are the historic norm, and the righting of a historic wrong, instead of a wrong done at the cost of human rights. It conceals the history of a region rich in its diversity and fluidity and its many peoples’ common heritage. It pretends that ethnic or religious identities are fixed and static, the main protagonists of history, instead of the passing and protean forms people adopt. It confuses a literary and political story with an account of how things happened and should be done. And it fortifies the neurotic siege mentality that typifies modern zionism, that thinks the Jewish people are a nation forever on the brink, hemmed in by existential evils on every side (including within), whose choice perennially is that between a death in exile or a life lived by the sword; and whose enemy is Amalek, the trans-historical oppressor, whom the Israeli public and prime minister love to identify with Palestinians, and whom the lord god dictates must be slain down to the last man, woman and child.

In possessing a scriptural corpus full of fabulation and propaganda, the Jewish tradition is surely not alone. And Jewish people, having been on the receiving end of other nations’ fantastic bigotries, were in some ways uniquely poised to be immune to nationalistic junk. But now this mythos forms the canon of the hegemonic religion, and frames the charter of a nation-state on a genocidal spree, and other aspects of the tradition gleam in an ironical new light. There is, for example, the story of a people in captivity or bondage, trapped in a lions’ den, estranged from their own land. They were held at the brutal mercies of the reigning kings of earth, who razed their holy sites and obliterated their homes. The horrors of this story, however historical it might be, are reenacted daily and broadcast for all the world to see. But it’s done now in that people’s name, and against that people’s kin, by the river and the sea of a new Babylon.

New York, 2024.